Health equity has been thrust into the spotlight with providers, regulatory agencies, and payers seeking ways to identify and eliminate disparities in care across race and ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and other lines. It is a priority further impacted by the emergence of new quality-based care models that go beyond those established under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

For example, in January 2023, the Global and Professional Direct Contracting (GPDC) Model will be replaced with the Accountable Care Organization Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (ACO REACH) Model, a test program designed to address health inequities and improve support for provider-led organizations in risk-based arrangements. It requires participants to address health disparities and support better health outcomes by:

- Reducing avoidable utilization

- Improving quality scores

- Ensuring safe care transitions

This includes the creation of a health equity plan, beneficiary-level risk adjustments, and collection of beneficiary-reported demographic and social determinants of health (SDOH) information that covers race, ethnicity, language, gender identity, and sexual orientation as required by the United States Core Data for Interoperability Version 2 (USCDI v2).

The challenge for many healthcare organizations that want to participate in new reimbursement models focused on achieving care parity is how to expand healthcare leaders’ view of health equity and SDOH to fully grasp the true reach of this vital data. This is necessary because the prevalent view focuses on initiatives related to patient experience and patient relations, which fails to consider how actionable data comes through as a natural occurrence of a patient’s interaction with the health system staff and care team.

Often overlooked is the fact that healthcare organizations’ coding and revenue cycle management (RCM) departments are already aggregating valuable information that can ultimately help identify and better understand inequities in care delivery and inform initiatives to improve health equity across their patient populations.

A Primer on SDOH Impacts

To set the stage for a deeper discussion on the role of RCM and coding in closing the health equity gap, consider the wide range of health risks and outcomes that are impacted by SDOH that make these data important predictors of clinical care and costs.

First, populations for analysis can be defined as anything from geographic, race, gender, and age to disability, health plan, or any other shared or defining characteristic. Once populations are defined and available data analyzed to compare outcomes, it becomes clear that health disparity within the United States is both significant and expanding. Smoking, obesity, gun violence, and teenage pregnancy are just a few of the health problems that are concentrated among the most vulnerable members of US society: the poor and less educated, as well as disadvantaged groups such as those with mental illness and substance use disorders and the homeless, incarcerated, and LGBTQ+ community.

Further, while social circumstances, genetic predisposition, environmental exposure, and behavioral patterns impact premature death, data shows that the single greatest opportunity to improve health and reduce premature death is personal behavior (the New England Journal of Medicine refers to “obesity and inactivity” and “smoking” as behavioral problems), which accounts for nearly 40 percent of all deaths in the US.

SDOH has also been linked negatively with such outcomes as higher hospital readmissions and length of stay (LOS), increased need for post-acute care including skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), long-term care (LTC), rehabilitation, and home health. As a result, value-based payment programs may penalize organizations that disproportionately serve disadvantaged populations.

Thus, monitoring for and addressing these socioeconomic issues that have a demonstrated impact on health is imperative to closing the nation’s health equity gap—with the added bonus of boosting healthcare organizations’ financial situations. For example, addressing food insecurity by linking patients to such programs as Meals on Wheels, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs (SNAP), or food pantries has been shown to reduce malnutrition rates and improve short and long-term health outcomes.

In the case of SNAP, which is the primary source of nutrition assistance for more than 42 million low-income Americans, participants are more likely to report excellent or very good health than low-income non-participants. Early access to SNAP among pregnant mothers and in early childhood improved birth outcomes and long-term health as adults, and elderly SNAP participants are less likely to forgo their full-prescribed dosage of medicine in favor of food due to expenses. Further, after controlling for factors expected to affect spending on medical care, on average, low-income adults participating in SNAP incur nearly 25 percent less in medical care costs (~$1,400) in a year than low-income non-participants.

Health Equity and RCM

Between the financial impact of addressing SDOH and the emergence of new reimbursement models that emphasize health equity, there is a strong business case to be made for involving RCM in any comprehensive health equity/SDOH strategy. Health disparities contribute $93 billion in excess medical care costs and $42 billion in lost productivity per year, along with additional economic losses due to premature deaths. If these inequities were eliminated by 2050, it would reduce the need for more than $150 billion in medical care.

Adding to the body of evidence supporting RCM involvement in the pursuit of health equity is the fact that reimbursement is closely linked to quality due to the use of outcome measures by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to determine a hospital’s overall quality, including mortality, safety of care, readmission rate, excess stay, patient experience, and effectiveness of care.

Readmission rates, utilization, and excess inpatient stays in particular tie back to SDOH:

- Low literacy is linked to poor health outcomes and less frequent use of prevention and wellness services, leading to more frequent and longer hospital stays.

- Lack of access to reliable transportation for basic health needs results in 41 percent more excess days in the hospital.

- Unemployment is linked to declining self-reported health status, increased mortality rates for males and females ages 16-64, quadruple rates of drug and substance abuse and dependence, and double the chances of being diagnosed with a mental disorder such as depression or general anxiety disorder.

These metrics are an important chapter of a patient’s SDOH story when physicians and other care team members take the time to enter comprehensive documentation in the patient’s chart. Thoughtful documentation allows coding professionals to assign appropriate codes for use in tracking and trending SDOH patterns, which allows healthcare organizations to better understand their patient populations. Further, because of the impact of SDOH on key CMS quality metrics, organizations that disproportionately serve disadvantaged populations may be penalized for participating in value-based payment programs.

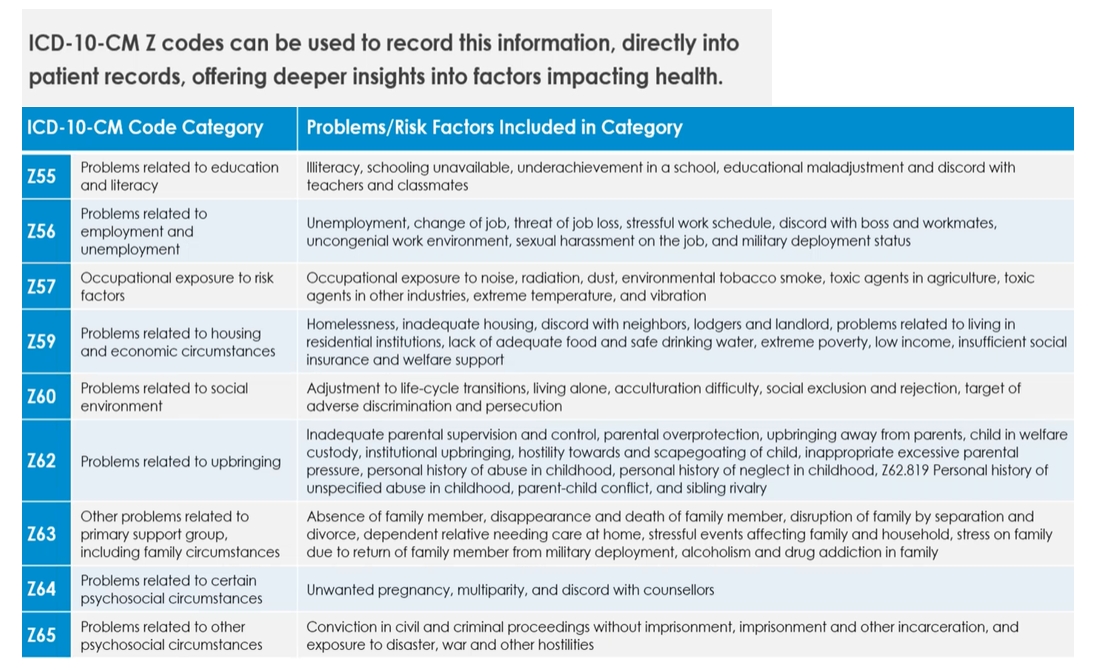

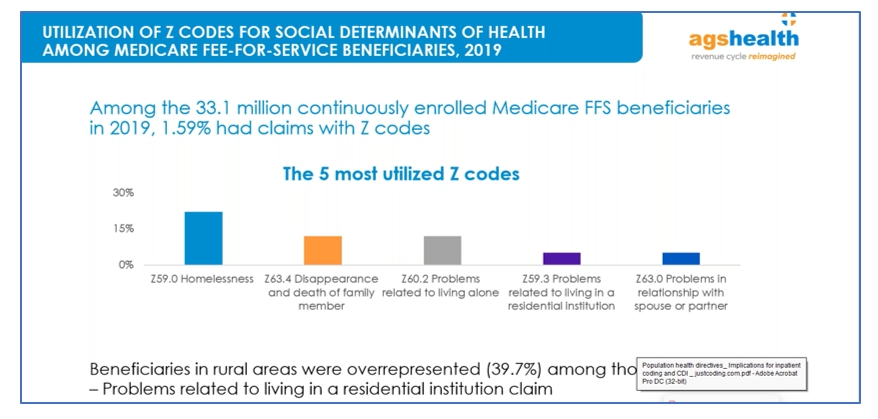

Coding and RCM professionals interact daily with information that is invaluable to inform health equity strategies, particularly since the transition to ICD-10 created an environment rich with data detailing SDOH. In fact, ICD-10-CM Z codes can be used to record highly detailed SDOH directly into the patient’s record, providing deeper insights into factors impacting health.

The top three most important factors for determining and addressing SDOH needs related to health outcomes are homelessness, food insecurity, and isolation. Documentation from third-party services like social and community health workers, case managers, nurses, and self-reported information is vital to painting a comprehensive portrait of a population’s SDOH. The ability to include this documentation within the patient’s official medical record is having a significant impact on addressing SDOH and narrowing the health equity gap.

With access to this depth of SDOH information, needs can be accurately assessed, and patients can be connected to community services to address them. Ultimately, when SDOH data is standardized within the electronic record, it not only improves health, lowers costs, and advances health equity, but it also enables healthcare organizations to develop sustainable business models to fund access to community services.

Closing the Gap

By integrating SDOH insights into care plans, clinical and community-based healthcare stakeholders can recognize the need for and enable patient access to additional services and/or interventions, such as programs that provide healthy food, reliable housing, or help patients manage isolation and loneliness, ultimately driving better health and wellness outcomes. Access to this depth of data helps improve timely discharges and reduce LOS and readmission rates.

The challenge lies in a provider’s ability to sift through the mountains of data already being collected to uncover valuable health equity insights. Doing so requires a carefully designed and implemented strategy that starts with establishing a governance committee tasked with designing policies and procedures to ensure SDOH needs are assessed, and patients are linked to the community services needed to address them.

Despite the critical role it plays in a successful approach to optimizing the use of the SDOH data aggregated as part of the RCM process, most healthcare organizations do not have a governance committee in place to oversee the use of this critical information. Of the 56 percent of organizations reporting in an AHIMA survey that they collected SDOH data, 73 percent said they had not established a governance committee. This is a critical oversight, as governance is imperative for making key determinations such as who is tasked with conducting patient assessments and how best to gather the data without creating yet another administrative burden.

Decisions also must be made on the best method for integrating the information into the patient’s electronic record to create a single source of information for coding professionals, as well as establishing metrics to track improvements to documentation supporting Z codes and SDOH over time. Finally, the committee must determine the best approach to connecting patients with the community services they need to address SDOH and ensure appropriate funding for ongoing access.

In addition to establishing a governance committee to lay out policies and procedures and oversee progress, healthcare organizations need to fully address four major data concepts to fully integrate SDOH with clinical data and care plans:

- Screening tools: Used to identify patients with social risk factors. There are numerous existing tools that can be leveraged, including some embedded within electronic health record systems.

- Diagnosis/Identified need(s): Reporting of SDOH issues that are identified by screening tools.

- Interventions: Actions that need to be taken to address the specific SDOH needs.

- Goals: Results expected to be achieved to resolve the patient’s identified need(s).

It is also important to conduct audits on documentation quality and coding accuracy and to provide feedback as appropriate. Finally, success requires data interoperability, a common set of values, and the capability to harness data for analytical purposes.

An Opportunity to Improve Care

Health equity is an industry-wide imperative that requires creative and collaborative problem-solving. Its status as a top priority is not expected to change in the coming years, as evidenced by CMS releasing its Framework for Health Equity and proposed rules to advance health equity.

As community stewards and centralized, life-saving hubs, healthcare providers can address more than basic catch-and-patch healthcare by exploring opportunities to eliminate disparities and improve care among underserved communities. The data aggregated daily by coding and RCM departments—particularly via detail-rich ICD-10-CM Z codes—can play a pivotal role in identifying and understanding population needs and aligning patients with necessary resources to address SDOH issues and close the health equity gap.

Leigh Poland (leigh.poland@agshealth.com) is vice president of AGS Health’s Coding Service.

By Leigh Poland, RHIA, CCS

Take the CE Quiz